French speakers of English are often perceived as having very nasal speech when they speak English.

By Sarah Beemer

Course: Language Sound Structures (Ling 3100)

Advisor: Prof. Rebecca Scarborough

LURA 2018

In most languages, including English, vowels that occur next to nasal consonants (m, n, and ng in English) are produced as slightly or entirely nasal. I saw this as phonetically interesting. In my research, I compared nasalized vowels before nasal consonants in the English speech of two first language (L1) speakers of English and two French second language (L2) speakers of English. My hypothesis was that the French L2 speakers would have more nasal vowels than the L1 speakers.

These vowels were investigated in the form of spectrograms, which are visual representations of a spectrum of sound over time. I also investigated the auditory perception of the vowels by a third party listener. The listener was not given any information about their task, and they simply listened to the words and described the vowels as nasal or not nasal. There were three ways to identify nasalization in the vowels: if the third party listener perceived the vowels as particularly nasal, if the spectrograms showed less noise in specific areas (between F1 and F2, also known as a nasal zero), and if the spectrograms showed a larger range of frequencies in specific places (increased bandwidth of F1).

I looked at the same five vowels for each speaker. I took my French L2 English speech from YouTube interviews of a famous French actor, Jean Reno, and a famous French actress, Catherine Deneuve. I recorded the English L1 speech myself and used the same sentences spoken by the L2 speakers in their interviews. This way I ensured that the vowels I compared would be the same, with the exception of accent.

In the end, my hypothesis was perceptually supported. The third party listener heard the French speakers’ vowels as more nasal than the native English speaker's vowels, and the male French speaker's vowels as nasal more often than the female French speaker's vowels.

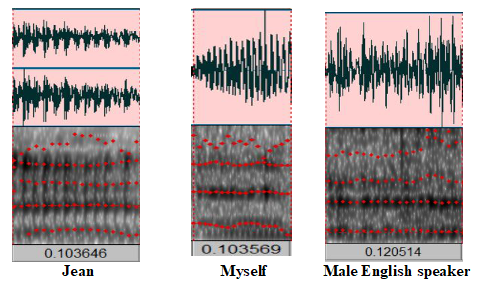

The spectrogram data reported both in favor of the hypothesis and against it. The nasal zeros (lack of noise between F1 and F2) were the most varied observations. The female French speaker's spectrograms showed a nasal zero 1/5 times, and the male French speaker showed a nasal zero 2/5 times. Below is a set of 3 spectrograms for a single vowel (/æ/) (1 for Jean Reno, and 1 for each English L1) in which a much lighter space (nasal zero) is seen between F1 and F2 of Jean Reno's vowel:

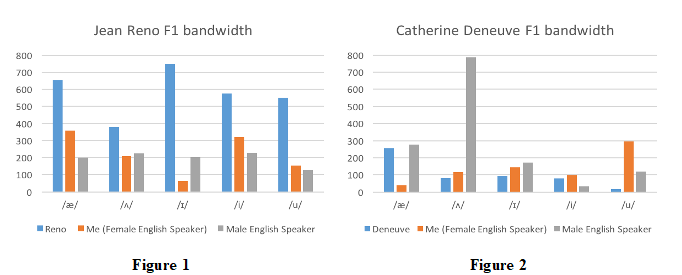

However, bandwidth data did support the hypothesis in regard to the male French speaker, but not in regard to the female French speaker as seen in Figures 1 and 2 below:

Some of the bandwidth data for English L1 speakers was much lower than expected. The majority of the spectrogram information did not support the hypothesis, but there was more support seen with Jean Reno's data than with Catherine Deneuve's. It is possible that nasal zero data is not as salient as bandwidth data in perception. It also turns out that the way people perceive speech sounds does not always correlate with the acoustic properties of those speech sounds, and as a result the bandwidth data is likely the most crucial.

There is an existing body of research on the human perception of speech sounds and how that perception is not always acoustically supported. It makes me wonder what it is about a French accent that lends people to perceive their vowels as more nasal when in reality they often are not. Because French has nasal sounds that are meaningfully contrastive, French speakers will be more perceptive of the presence or absence of nasal sounds. My new hypothesis is that this may very well have an effect on the way French L1 speakers speak English and they may have more conscious control over the presence of co-nasalization. Even though the hypothesis was not fully supported and some of the data was inconclusive, I still learned a lot in the process of doing this research.

Ìý

Sarah Beemer is a Junior undergraduate student working on her BA in Linguistics with a Classics minor. She endeavors to be accepted into the BA/MA program after this semester and pursue an MA in Linguistics. Her current main interests include Latin, semantic and pragmatic theories, language reconstruction, etymology, and linguistic relativity. She also does metalworking and jewelry, knits, sings, and plays guitar in her free time.

Sarah Beemer is a Junior undergraduate student working on her BA in Linguistics with a Classics minor. She endeavors to be accepted into the BA/MA program after this semester and pursue an MA in Linguistics. Her current main interests include Latin, semantic and pragmatic theories, language reconstruction, etymology, and linguistic relativity. She also does metalworking and jewelry, knits, sings, and plays guitar in her free time.